Dongbeihua — The Dialect of North-East China

Learn to speak like the locals

A Textbook for Foreigners

‚Dongbeihua’ (东北话) is the common Chinese term for the Standard Chinese dialect spoken in North-East China. It earned some fame within Mainland China due to its strong presence in national TV shows and sketches over the last twenty years.

The North-Eastern dialect is distinguished from Standard Chinese mainly in terms of different words and expressions, many of which have been influenced by the Altaic language of the Manchu and by the Chinese dialect spoken by settlers from Shandong province. The most common and interesting words and expressions have been collected and described in this book.

About Dongbeihua: |

For most of its history, North-East China has been homeland of the Manchu people, a Southern Tungusic nation whose language is part of the Altaic language family, and as such is remotely related to the Mongolian, Turkic, and possibly the Korean and Japanese languages. The script used to write Manchu has been derived from the Mongolian script and is generally written from the top to the bottom, and from the left to the right, with letters having different forms depending on their positions and the preceding or succeeding vowels. In the north and east of Manchuria, several Siberian tribes, among them several Tungusic speaking peoples, had settled before the arrival of Russian settlers. In the south, Manchuria borders North Korea, and Korean minorities have been living north of the borders for centuries, both in the countryside (e.g. 长白朝鲜族自治县 Changbai Korean Autonomous County) as well as in cities (e.g. 西塔 xītǎ Korean town in Shenyang). In the west of Manchuria, various Mongolian tribes have settled, today the area is split into Inner Mongolia, belonging to the People’s Republic of China, and Outer Mongolia, an independent state. In the south-west of Manchuria lies the heartland of China with the Han-Chinese majority who originated from areas close to the Yellow River and whose language is part of the Sino-Tibetan language family and as such remotely related to the Tibetan language, but not to the languages of the Mongolian, Manchu, or Uyghur ethnic minorities.

The area gained worldwide relevance when the Manchu, well versed in horse riding and archery, defeated the Ming dynasty in 1644 and established the ‘Qing’ dynasty. The Manchu banner men (八旗 bāqí) were sent to all parts of China for purposes of political and military administration, and their descendants today form a small number of ethnic minorities, even in remote parts of China, such as Yunnan (<0.01%) and Xinjiang (0.1%). On the one hand, the comparatively small number of Manchu people imposed several customs on the non-Manchu subjects, such as the traditional male hair dress with a shaved front head and long plait at the back, or the famous banner dress (旗袍 qípáo) which became particularly famous with Chinese ladies.

On the other hand, the Manchus, both inside and outside of Manchuria soon took on the Chinese language and culture. At the end of the Qing dynasty, the Manchu language was scarcely spoken in daily life and played a similar role to the ‘dead’ Latin language in the Europe of the 20th century. Until 1859, the homeland of the Manchu itself was forbidden to Han-Chinese settlers and blocked by the Shanhai pass (山海關 shānhǎiguān) near Qinhuangdao, but from 1859 until 1930, many waves of Han-Chinese, mainly from the Shandong and Hebei provinces, ‘popped’ through the opened pass (闯关东 chuǎng guāndōng) to settle in Manchuria, thereby sinicising the area, and rendering the Manchu as an ethnic minority within North-East China. With the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the humiliations inflicted on the Chinese by European and Japanese imperialism, the Manchus were blamed for the decay of China, and several Han-Chinese riots against Manchu people followed. This antipathy towards Manchu people and culture intensified when the last emperor, 溥儀 Pǔ Yí, whose mother language was Chinese and not Manchu, established a Japanese puppet regime in the separatist state of Manchukuo from 1932-45. Today, Manchu people account for less than 13% of the population in North-East China and, besides the Sibe (锡伯 xíbó) tribe in the Xīnjiāng province speaking a dialect of Manchu, only about 20 elderly people in some remote villages in Heilongjiang and Fushun still speak Manchu fluently. The Manchu language, thus, became a scholarly language for those interested in the last dynasty of the Chinese empire. Because of the role Manchus played in the fall of the Chinese empire and in the war with Japan, the term ‘North-East China’ is widely preferred to ‘Manchuria’ and the language spoken today in North-East China is a Chinese Mandarin dialect influenced by a Manchu substratum and called ‘North-Eastern Chinese’ (东北话 dōngběihuà). Since the Manchu soon after conquering China proper moved their capital from Shenyang to Beijing, there are several similarities between Dongbeihua and the Beijing dialect of Chinese: Several Manchu influenced terms like 马马虎虎 mǎmǎhūhū have been neglected in this book, as they are equally used in Dongbeihua and the Peking dialect, and, the latter being the basis for Standard Chinese, known and used throughout China. It is often believed that certain peculiarities in the Northern Chinese dialects which do not exist in Southern Chinese dialects stem from the Manchu language. The distinction between ‘we (excluding you)’ and ‘we (including you)’ exists in Manchu (ᠪᡝ be vs. ᠮᡠᠰᡝ muse), and Northern Chinese (我们 wǒmen vs. 咱们 zǎnmen), but not in Southern Chinese dialects like the Shanghai dialect, or Cantonese.

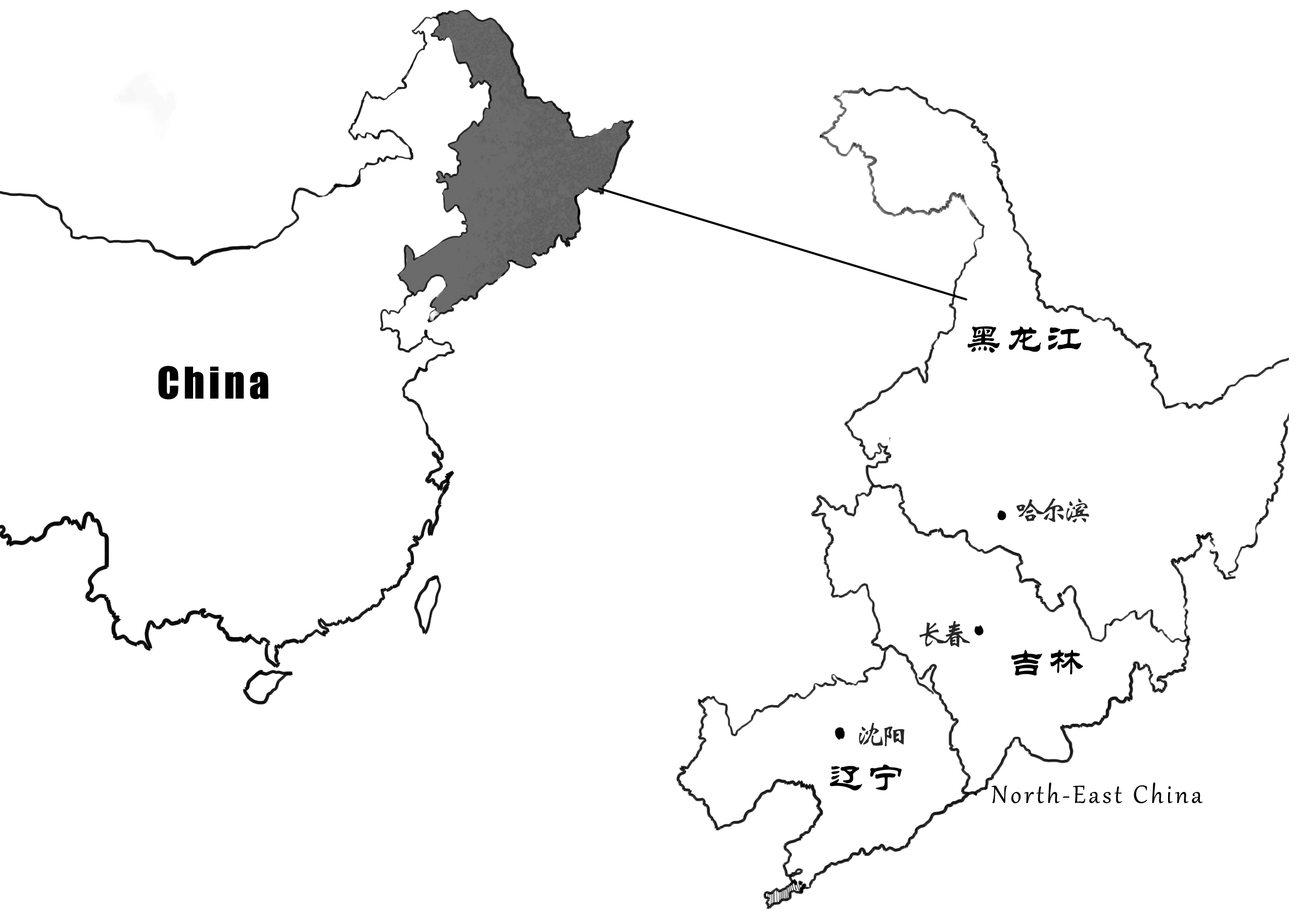

Today, Dongbeihua is mainly spoken in what is commonly referred to as North-East China (东北 dōngběi), made up of the three Chinese provinces of

- Heilongjiang (north) with the provincial capital Harbin,

- Jilin (centre) with the provincial capital Changchun, and

- Liaoning (south) with the provincial capital Shenyang.

The southern coastal areas around Dalian and Dandong have historically strong connections to the Shandong peninsula, and, although belonging to North-East China, people living there generally do not speak Dongbeihua, but a distinctly different dialect of Mandarin.

Due to the large mobility of the Chinese society, differences between the dialects of the three provinces are comparatively low. In a simplifying manner, one could state that the strongest Dongbeihua is spoken in Liaoning province in and around Shenyang, as Shenyang, or ᠮᡠᡴ᠋ᡩᡝ᠋ᠨ mukden as it is called in Manchu, is the historic capital of the Manchu people, and the influence of the Manchu language seemed to be the most intense in this area. Changchun, on the other hand, was the capital of the separatist Manchu puppet state Manchukuo controlled by the Japanese between 1932 and 1945, and the influence of the Japanese language seems stronger than in Liaoning and Heilongjiang. Finally, the language spoken in and around Harbin is known to be closer to Standard Chinese than the language of Shenyang and Changchun. However, due to the proximity to the Russian border, some minor Russian influence on the vocabulary can be denoted, such as the rare 裂巴 lièba ‚Western bread‘ from the Russian хлеб, and 马神 mǎshén ‚machine‘ from the Russian машина.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, Dongbeihua can be generally identified my most inhabitants of mainland China. A reason for this is that Zhào Běnshān (赵本山), a famous comedian and TV star from Tieling, Liaoning province, has for more than twenty years regularly performed sketches in Dongbeihua on China’s state television. Also, Chinese television regularly hosts singers of the famous North-Eastern art of ‘two-people rotation’ dances (二人转 èrrénzhuǎn), a singing performance by man and women about topics that range from the everyday down to the suggestive. In the perception of contemporary Chinese, Dongbeihua thus conveys a sense of masculinity, ease, and humour, and is as such comparable to the role that the famous North-Eastern German dialect of Eastern Prussia plays for the German language..

About the Author: |

Dennis Behnke (熊德明) is working as a management and engineering consultant in China. Since his secondary education in Germany, he has been passionate about the study of foreign languages and cultures.

From the Content: |

Lesson 1 — The Basics

1. 哈 há

2. 嘎 gà/嘎哈 gà há

3. 嗯呐 ēnne

4. 咋 zǎ/咋地 zǎ di

5. 整 zhěng

6. 使 shǐ

7. 扯 chě (扯淡 chědàn)

8. 哎呀妈呀 áiyā māya

9. 俺 ǎn

10. 庸乎 yōnghu

11. 个六 ge liù (cf. Manchu ᡤᡝᠯᡳ geli)

12. 老 lǎo

13. 蛮子 mánzi

14. 贼 zéi

15. 必 bì

16. 钢钢 gānggāng/杠杠 gǎnggǎng

17. 瞅 chǒu

18. 删/扇 shān/散 sǎn/闪 shǎn

19. 削 xiāo

20. 忿 fèn

21. 干仗 gànzhàng

22. 侅 gāi (cf. Manchu ᡤᡳᠶᠠᡳ giyai)

23. 巴拉儿 bālā’r (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠᠯᠠ balain)

24. 溜达 liūda (cf. Manchu ᠯᡝᡵ)

25. 哪块儿 nǎ kuài’r

26. 马路牙子 mǎlu yázi

27. 打车 dǎchē

28. 卡 kǎ (cf. Manchu ᡴᠠᠯᡨ᠋ᠠᡵᠠᠮᠪᡳ kaltarambi)

29. 揍 zòu

30. 拽 zhuāi

31. 备不住 bèibuzhù

32. 兴许 xīngxǔ

33. 八成 bāchéng

34. 十成 shíchéng

35. 准成 zhuňchéng

36. 老鼻子 lǎobízi

37. 土鳖 tǔbiē

38. 山炮 shānpào

39. 土得掉渣儿 tǔ-de diào zhā’r

40.丫蛋儿 yādàn’r, 闺女 guīnǚ

41. 自个儿 zìgè’r

42. 铁子 tiězi

43. 哥们儿 gēmen’r

44. 老爷们儿 lǎoyèmen’r

45. 老娘们 lǎoniángmen’r

46. 二椅子 èryǐzi

47. 尬点儿 gà diǎn’r (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᡥᡡᠮᠪᡳ gahūmbi)

48. 嘎拉哈 gǎlahà/嘎达哈 gǎdahà (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠴᡠᡥᠠ gacuha)

49. 点儿正 diǎn’r zhèng

50. 点儿背 diǎn’r bèi

51. 点儿 diǎn’r

52. 前儿(个) qián’r (ge),

昨儿(个) zuó’r (ge), 夜儿(个) yè’r (ge)

今儿(个) jīn’r (ge),

明儿(个) míng’r (ge),

后儿(个) hòu’r (ge).

53. 晌午 shǎngwǔ, 吃晌 chīshǎng

54. 朝天 cháotiān

55. 在早 zài zǎo

56. 早不两天 zǎo bù liǎng tiān

57. 立马 lìmǎ

58. 眼目前儿 yǎnmu qián’r

59. 晃常儿 huàng cháng’r

60. 盯巴儿 dīng bā’r (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠ ba)

61. 彪 biāo

62. 抠 kōu

Lesson 2 — Intermediate Level

63. 划拉 huála (cf. Manchu ᡥᡡᠸᠠ hūwa, ᡥᡡᠸᠠᠯᠠᠮᠪᡳ hūwalambi)

64. 敞亮 chǎngliang

65. 朝面儿 cháo miàn’r

66.寸劲儿 cùnjìng’r

67. 走一个 zǒu yī ge

68. 整两口 zhěng liǎng kǒu

69. 提另格儿 tílìng gé’r (cf. Manchu ᡝᠮᡨᡝᠩᡤᡝᡵᡳ emtenggeri)

70. 掌柜的 zhǎngguìde, 老板娘 lǎobǎniáng

71. 酒蒙子 jiǔméngzi

72. 酒漏 jiǔlòu

73. 敞开儿 chǎngkāi’r

74. 霸道 bàdao

75. 掺和 c(h)ānhuo

76. 必须的 bìxūde

77. 雪糕 xuěgāo

78. 毛磕 máokē

79. 好赫儿 hǎohè’r

80. 味素 wèisù (cf. Japanese 味の素).

81. 苞米 bāomǐ

82. 水舀子 shuǐyǎozi

83. 吧唧 bājī, 吧唧(嘴) bājī(zuǐ)

84. 包圆儿 bāoyuán’r

85. 整个浪儿 zhěnggè làng’r

86. 噶气 gáqì

87. 反噔 fǎndeng, 翻腾 fānteng

88. 吃伤了 chīshāng le

89. 洋火 yáng huǒ

90. 该着 gāizháo

91. 吧吧苦 bābā kǔ

92. 齁齁咸 hōuhōu xián

93. 佼佼酸 jiǎojiǎo suān

94. 顺顺甜 shùnshùn tián

95. 吱儿吱儿辣 zī’r zī’r là

96. 串烟了 chuànyān le

97. 哈拉味儿 hālā wèi’r (cf. Manchu ᡥᠠᠯᠠᠮᠪᡳ halambi)

98. 糗了 qiǔ le

99. 茅楼 máolóu, 便所 biànsuǒ

100. 出外头去 chū wàitou qù

101. 粑粑 bābā (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠ ba), 蹲 dūn

103. 氽稀 tǔnxī, 蹿稀 cuānx

104. 开腚 kāidìng, 拔干 bágān

105. 军大衣 jūndàyī, 棉猴儿 mián hóu’r, 棉袄 mián’ǎo

106. 校哔 xiàobì

107. 踏拉板儿 tǎlāban’r (cf. Manchu ᡨ᠋ᠠᠯᠠᠪᡠᠮᠪᡳ talabumbi)

108. 拔缯子 bázèngzi

109. 抽巴 chōuba

110. 捣扯 dǎoche

111. 寒碜 hánchen (cf. Manchu ᡥᡝᠨᠴᡝᠮᠪᡳ hencembi, ᡥᡝᠴᡝᠮᠪᡳ hecembi)

112. 砢碜 kēchen (cf. Manchu ᡝᡴ᠌ᠴᡳᠨ ekcin, ᡴᠠᡵᠴᠠᠮᠪᡳ karcambi)

113. 稀罕 xīhan (cf. Manchu ᠴᡳᡥᠠᠯᠠᠮᠪᡳ cihalambi)

114. 秀眯 xiùmi (cf. Manchu ᡥᡳᡧᡡᠨ hišūn)

115. 看对眼儿了 kàn duì yǎn’r le

116. 打光棍儿 dǎ guāng gùn’r, 光杆子 guānggǎnzi

117. 嚼情 jiáoqing

118. 啄嘴儿 zhuó zuǐ’r

119. 搂脖抱腰 lǒubó bàoyāo

120. 办事儿 bànshì’r

121. 粘乎 niánhu

122. 对撇儿 duìpiězi

123. 撩骚 liáosāo

124. 撸管子 lū guǎnzi

125. 老蒯 lǎokuǎi

126. 老头子 lǎotóuzi

127. 臊性 sāoxing

128. 养汉 yǎnghàn

129. 搞破鞋 gǎo pò xié

130. 叽咯 jīge (cf. Manchu ᠵᡝ ᠵᠠ je ja, ᡤᡝᡵ ᡤᠠᡵ ger gar)

131. 整事儿 zhěng shì’r

132. 掰交儿 bāi jiāo’r

133. 奔儿楼 bén’r lóu

134. 哈喇子 hálázi

135. 鼻汀 bítīng

136. 玻棱盖儿 bōlenggài’r (cf. Manchu, ᠪᡠᠯᠠᠩᡤᠠ bulangga)

137. 胳棱盖儿 gēlenggài’r (cf. Manchu ᡤᡳᡵᠠᠩᡤᡳ giranggi)

138. 渣儿 zhā’r

139. 牛子 niúzi

140. 懒子 lǎnzi

141. 大肠头 dàchángtóu

142. 嘎挤窝 gájǐwo

143. 刺挠 cìnao

草溜子 cǎoliūzi

145. 长虫 chángchóng

146. 潮虫 cháochóng

147. 当棱儿 dāngléng’r

148. 蚂蚱 màzha

149. 黄皮子 huángpízi

150. 家鸟儿 jiā qiǎo’r

151. 骒马 kèmǎ

152. 骚马 sāomǎ

153. 山狸子 shānlízi

154. 蚂蛉 mālíng

155. 老鹞子 lǎoyàozi

156. 老蟑 lǎozhāng

157. 瞎虻xiāméng

158. 胳能 gēneng (cf. Manchu ᡤᡝᠨᡝᠮᠪᡳ genembi)

159. 盖被乎 gài bèihu (cf. Manchu ᡥᡡ hū‚ ᡥᡠᠶᡝ huye)

160. 外屋地 wàiwūdì

161. 碗架子 wǎnjiàzi

162. 干巴地 gānbā de

163. 愉作 yúzuo

164. 日头 rìtou

嘎嘎冷 gāgā lěng

165. 洋车子 yángchēzi

166. 屁驴子 pìlǘzi

167. 三轮蹦子 sanlún bèngzi, 三驴蹦子 sanlù bèngzi

168. 旮旯儿 gālá’r (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠯᠠ gala)

169. 旮嗒 gāda (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᡩ᠋ᠠ)

170. 祸祸 huòhuo (cf. Manchu ᡥᡡᠸᠠᠰᠠ ᡥᡳᠰᠠ hūwasa hisa)

171. 唠嗑 làoke

172. 坐地炮 zuòdìpào

173. 老倒子 lǎodǎozi

174. 拉咕 lágu

175. 二道贩子 èrdào fànzi

176. 埋汰 máitai

177. 立整 lìzheng, 利索儿 lìsuo’r

178. 马葫芦 mǎhúlu (cf. English ‚manhole’)

179. 卖呆儿 mài dāi’r

180. 邪呼 xiéhu

181. 吃独食儿 chīdú shí’r

182. 尿性 niàoxìng

183. 白扯 báichě (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠᡳᡳᡥᡠ baihu)

184. 得瑟 dèse (cf. Manchu ᡩ᠋ᡝ᠋ᠰᡳ desi)

185. 矬把子 cuóbàzi

186. 诡道/鬼道 guǐdao

187. 先头儿 xiān tóu’r

188. 张罗 zhāngluo

189. 稀里马哈 xīlǐmǎha (cf. Manchu ᠴᡳᠮᠠᡥᠠ cimaha)

190. 毛愣 máoleng

191. 呲溜 cīliū

192. 秃噜 tūlu 1 (cf. Manchu ᡨᡠ᠋ᠯᡳᠮᠪᡳ tulimbi)

秃噜皮/毛 tūlu 2 pí/máo (cf. Manchu ᡨᡠ᠋ᠯᡠᠮ tulum)

193. 抓瞎 zhuāxiā

194. 愣头青 lèngtóuqīng

195. 麻溜 máliu

196. 煞愣 shāleng’r

197. 磨叽 mòji (cf. Manchu ᠮᡠᠵᡳ muji)

198. 劈儿片儿 pī’r piàn’r (cf. Manchu ᡦᡠᠯᡠ ᡦᠠᠯᠠ pulu pala)

199. 撂秆子 liào gǎnzi, 蹽杠子 liāo gàngzi

200. 叫叫 jiàojiào

201. 抻头 chēntou

202. 吊儿郎当 diào’r lángdāng

203. 掰扯 bāiche (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠᡳᡳᡨ᠋ᠠ baita)

204. 别别 biébie

205. 吃不住劲 chībuzhùjìn

206. 约摸 yāomo (cf. Manchu ᡤᡡᠨᡳᠮᠪᡳ gūnimbi)

大约摸 dàyāomo/大约母 dàyāomu

大估景 dàgūjǐng

207. 寻思 xúnsi

208. 解乎 xièhu

209. 鼓秋 gǔqiu (cf. Manchu ᡤᠣᠴᡳᠮᠪᡳ gociimbi, ᡤᡠᠪᠴᡳ gubci, ᡤᡠᠵᡠᠩ ᠰᡝᠮᡝ gujung seme)

210. 鼓捣 gǔdao (cf. Manchu ᡤᠣᡩ᠋ᠣᠮᠪᡳ godombi)

211. 忙叨 mángdao

212. 狠叨 hěndao (cf. Manchu ᡥᡝᠨ᠋ᡩᡠ᠋ᠮᠪᡳ hendumbi)

213. 嘚啵 dēbo

214. 带劲 dàijìn

215. 曲咕 qūgu

216. 现眼 xiànyǎn

217. 悬乎 xuánhu

218. 各应 gèyìng (cf. Manchu ᡤᡝᠶᡝᠨ geyeng)

219. 惹乎 rěhu

220. 急眼 jíyǎn

221. 杠叽 gàngjī (cf. ᡤᠠᠨᠵᡳᠮᠪᡳ ganjjimbi)

222. 二串子 èrchuànzi

223. 滚犊子 gǔndúzi (cf. Manchu ᡤᡡᠯᡩᡠ᠋ᠨ gūldun)

224. 还愿地 huányuànde

225. 电炮 diànpào

226. 搬倒 bāndǎo

227. 吵儿八火 chǎo’r bāhuǒ (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠᡳᡳᡥᡠ baihu)

228. 咯叽 géji (cf. Manchu ᡤᡝᠵᡳᡥᡝᡧᡝᠮᠪᡳ gejihešembi)

229. 浑儿画儿 hún’r huà’r

230. 泡汤了 pàotāngle

231. 扎刺儿 zhācì’r

232. 嘞嘞 lēle

233. 鸟悄 niāoqiao

234. 眼力见儿 yǎnlì jiàn’r

Lesson 3 — Advanced Level

235. 五迷三道 wǔmí sāndào

236. 急赤歪脸 jíchì wāiliǎn (cf. 急头白脸 jítóu báiliǎn)

237. 火赤燎地 huǒchì liáode

238. 抠抠搜搜 kōukōu sōusōu (cf. Japanese こそこそ koso koso)

239. 二虎八鸡 èrhǔ bājī (cf. Manchu ᡝᡳᡳᡥᡠᠨ eihun, ᡝᡳᡥᡝᠨ eihen, ᠪᠠᠵᡳ baji)

240. 吭哧瘪肚 kēngchī biědù (cf. Manchu ᡴᡝᠩ keng)

241. 旮旯古气 gālá gǔqì (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠯᠠ gala, ᡤᡠᠪᠴᡳ gubci)

242. 疯疯张张 fēngfēng zhāngzhāng

243. 披哩扑鲁 pīlǐ pūlǔ (cf. Manchu ᡦᡠᠯᡠ ᡦᡳᠯᠠ pulu pila, ᡦᡠᠯᡠ ᡦᠠᠯᠠ pulu pala, ᡦᠠᡳᠯᡠ pailu)

244. 便宜搂收 piányi lóushōu

245. 嗷嗷贵 áoáo guì

246. 菜不结籽 càibù jiézǐ

247. 急了拐弯 jíle guǎiwān

248. 犄角旮旯 jījiǎo gālá (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠯᠠ gala)

249. 武马长枪 wǔmǎ chángqiāng

250. 费劲扒拉 fèijìn bālā (cf. Manchu ᡩᠠᠪᠠᠯᠠ dabala)

251. 破马张飞 pòmǎ zhāngfēi

252. 疙不溜脆 gābù liūcuì (cf. Manchu ᡤᡝᠪᡠ gebu, ᠯᠣᡧᡳᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ lošilembi)

253. 应时应晌 yīngshí yīngshǎng

254. 指牌落地 zhǐ pái luòdì

255. 呼哧带喘 hūchī dàichuǎn

256. 扬了二怔 yángle èrzhèng (cf. Manchu ᡝᡧᡠᠨ ešung, ᠠᡵᠵᠠᠨ arjang, ᠶᠠᠩᡤᡳᠯᠠᡥᠠ yanggilaha)

257. 楞的忽地 lèngde hūdì

258. 无机六瘦 wújī liùshòu (cf. Manchu ᠯᠣᡧᡳᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ lošilembi, ᠯᡝᠰᡠᠮᠪᡳ lesumbi‚ ᠯᡳᠯᠴᡳ lilci)

259. 突鲁反仗 tūlǔ fǎnzhàng (cf. Manchu ᡨᡠ᠋ᠯᡝ tule, ᡨᡠ᠋ᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ tulembi, ᡶᠠᠵᠠᠨ fajang)

260. 半拉咔叽 bànla kǎjī (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠵᡳᠮᠪᡳ gajimbi)

261. 鼓鼓求求 gǔgǔ qiúqiú

262. 罗锅拔象 luóguō báxiàng

263. 七吃咔嚓 qīchī kǎc(h)ā

264. 八犟眼子 bājiàng yǎnzi

265. 处决横丧 chǔjué héngsāng

266. 毛愣三光 máoleng sānguāng

267. 胎胎歪歪 tāitāi wāiwāi

268. 水裆尿裤 s(h)uǐdāng niàokù

269. 踢哩趿拉 tīle tālā

270. 咋咋哄哄 zhāzha hōnghong

271. 暴土扬灰 bàotǔ yánghuī, 暴土扬场 bàotǔ yángchǎng

272. 冒烟故嘟 màoyān gūdū (cf. Manchu ᠨᡳᠩᡤᡠᡩᡝ᠋ ninggude)

273. 赌气冒烟 dǔqì màoyān (cf. Manchu ᡩ᠋ᡠ᠋ᠰᡳᠮᠪᡳ dusiimbi)

274. 旮旯胡同 gālá hútòng (cf. Manchu ᡤᠠᠯᠠ gala)

275. 稀淌哗漏 xītǎng huālòu, 稀淌寡水 xītāng guǎshuǐ

276. 埋了八汰 máile bātài

277. 五雷嚎风 wǔléi háofēng, 捂了嚎风 wǔle háofēng

278. 咋咋唬唬 zhāzha hǔhu (cf. Manchu ᠰᡠᡵᡝᠮᡝ ᡥᡡᠯᠮᠪᡳ sureme hūlambi)

279. 哭丧脸儿 kūsangliǎn’r

280. 舞舞抓抓 wǔwu zhuāzhua

281. 眼泪巴叉 yǎnlèi bāc(h)ā (cf. Manchu ᠪᠠᡥᠠᠴᡳ bahaci, ᠪᠠᠴᡳᡥᡳ bacihi)

282. 紫了皓青 zǐle hàoqīng (cf. Manchu ᡥᠣᠵᠣ hojo)

283. 着急忙慌 zháojí mánghuāng

284. 蒙天海地 mēngtiān hǎidì

285. 扑愣蛾子 pūleng ézi

286. 血呼大涨 xuèhū dàzhǎng

287. 屁屁溜溜 pìpì liūliū (cf. Manchu ᡦᡳᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ pilembi, ᠯᡝᠣᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ leolembi)

288. 二溜八蛋 èrliú bādàn

289. 二溜子 èrliúzi, 二愣子 èrléngzi

290. 虚头八脑 xūtóu bānǎo

291. 扯哩哏儿棱 chěli gen’r lēng (cf. Manchu ᠰᡝᠩᡤᡝᠯᡝᠩᡤᡝ senggelengge)

292. 车轱辘话 chēgūlù huà (cf. Manchu ᠴᡝᡴᡠᠯᡝᠮᠪᡳ cekulembi)

Buy the Book: |